You are here

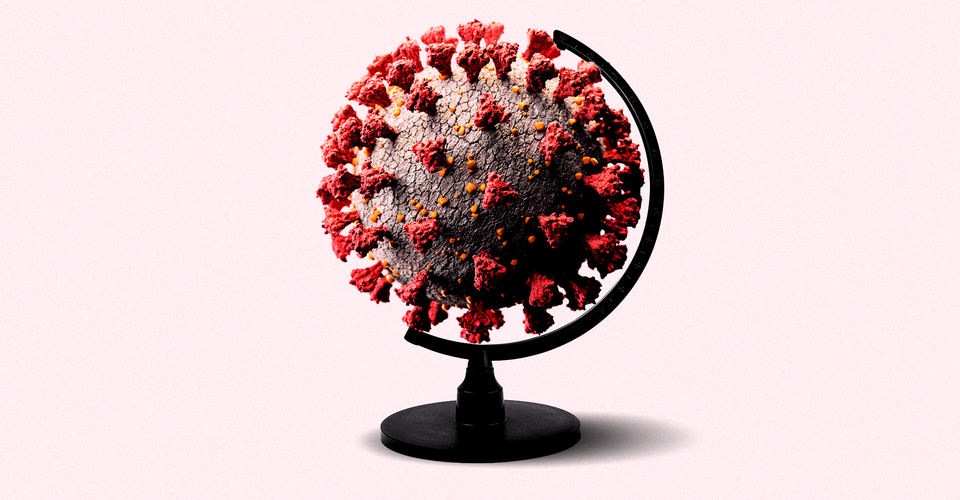

Will Omicron Leave Most of Us Immune? The variant is spreading widely, but won’t necessarily give us strong protection from new infections. The Atlantic

Will Omicron Leave Most of Us Immune? The variant is spreading widely, but won’t necessarily give us strong protection from new infections. The Atlantic Even before Omicron hit the United States in full force, most of our bodies had already wised up to SARS-CoV-2’s insidious spike—through infection, injection, or both. By the end of October 2021, some 86.2 percent of American immune systems may have glimpsed the virus’s most infamous protein, according to one estimate; now, as Omicron adds roughly 800,000 known cases to the national roster each day, the cohort of spike-zero Americans, the truly immunologically naive, is shrinking fast.

Virginia Pitzer, an epidemiologist at Yale’s School of Public Health and one of the scientists who arrived at the 86.2 percent estimate, has a guess for what fraction of the U.S. population will have had some experience with the spike protein when the Omicron wave subsides: 90 to 95 percent.

The close of Omicron’s crush, then, should bring the country one step closer to hitting a COVID equilibrium in which SARS-CoV-2’s still around, but disrupting our lives far less. In the most optimistic view of our future, this surge could be seen as a turning point in the country’s population-level protection. Omicron’s reach could be so comprehensive that, as some have forecasted, this wave ends up being the pandemic’s last.

But there is reason to believe that this ultra-sunny forecast won’t come to pass. “This wave will not be the last,” Shane Crotty, of the La Jolla Institute of Immunology, told me. “There are not many things that I am willing to be pretty confident about. But that’s one of them.” A new antibody-dodging variant, for one, could still show up to clobber us. And nearly everyone having some form of spike in their past isn’t as protective as it might sound. In a few months’ time, American immune systems will be better acquainted with SARS-CoV-2’s spike than they’ve ever been.

But 90 to 95 percent of people exposed doesn’t translate to 90 to 95 percent protected from ever getting infected or sick again; more immune doesn’t have to mean immune enough. By the time the country exits this wave, each of our bodies will be in radically different immunological spots—some stronger, some weaker, some fresher, some staler. Chart that out by demography and geography, and the defensive matrix only gets more complex: Certain communities will have built up higher anti-COVID walls than others, which will remain relatively vulnerable.

The malleability of the virus and the United States’ patchwork approach to combatting it has always meant that COVID would spread unevenly. Now the sums of those decisions will be reflected by our immunity. They’ll dictate how our next tussle with the virus unfolds—and who may have to bear the brunt of it.

Collective immunity is the key to ending a pandemic. But its building blocks start with each individual. By now we know that immunity against the coronavirus isn’t binary—and while no one can yet say exactly how much more protection Person A (triple vaxxed, recently infected) might have than Person B (twice infected, once vaxxed) or Person C (once infected, never vaxxed), we have figured out some of the broad trends that can toggle susceptibility up or down. Allowing for shades of gray, a person’s current immune status hinges on “the number of exposures [to the spike protein], and time since last exposure,” John Wherry, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania, told me. Infections and vaccinations add protection; time erodes it away. ...

Recent Comments